“No More a Man’s World Than It Is a White World” - Part 1

Women and Their Positions, Sixty Years Ago and Today

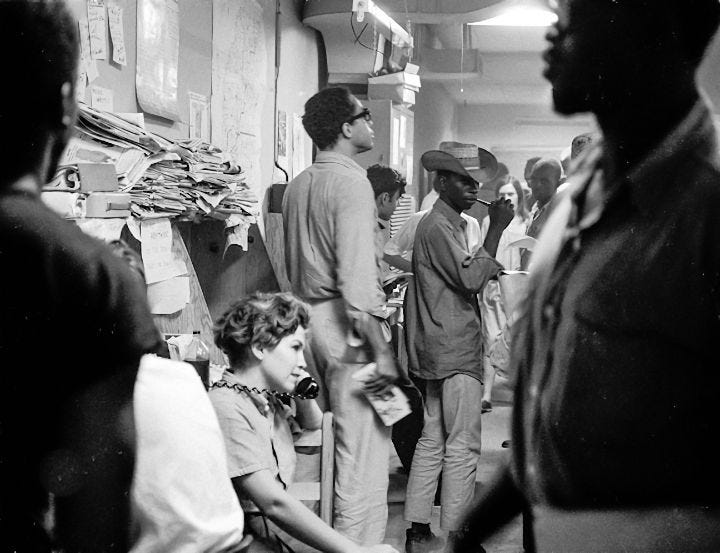

Mary King doing a woman’s task among men of the Freedom Movement (1964)

It is the support of readers like you that makes this publication possible. These essays are the result of a good deal of work. I rely upon voluntary supporters to keep going. I encourage you to become a paid subscriber, and to share this with others. Click here to become a paid subscriber:

“Assumptions of male superiority are as widespread and deep rooted and every much as crippling to the woman as the assumptions of white supremacy are to the Negro.”

—SNCC Position Paper (November 1964)

Sixty years ago this week, in the wake of a presidential election that had a dramatically different result from the one we just went through, members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) gathered at Waveland on the Mississippi Gulf Coast to review, reevaluate, and rejuvenate after what had happened during the recent Mississippi Summer Project (“Freedom Summer”).

Six decades later, those of us who believe in the promise of America—the radical ideals of equality and freedom enunciated in 1776—find ourselves in need of doing something similar, and the point made in the quotation above from an “anonymous” (the authors were almost immediately identified as Mary King and Casey Hayden) position paper on “Women in SNCC” speaks powerfully to us today, when we have just experienced millions of Americans voting for a totally unfit buffoon who boasts about his ability to sexually assault women, constantly promotes hate and division, sides with billionaires over ordinary people, says he wants to be a dictator, sides with the enemies of America and democracy … and much more rather than vote for an obviously competent woman—for the second time in eight years.

NOTE: This is Part 1 of the sixteenth in a series of essays, “The Long 1964 at Sixty,” I am writing on what was happening in what I term the Long 1964, “The Year ‘The Sixties’ Arrived and the Battle Lines of Today Were Drawn,” as I put it in the subtitle of my most recent book, The Times They Were a-Changin’. Portions of them will be taken straight from the book, but other parts of the essays will be new commentary.

This one introduces the issues of race and sex as they were playing out in the civil rights movement in 1964, especially in the Mississippi Summer Project, and ties them to deeper currents in human history. These tensions are very much still with us in the 2020s, and the authoritarian movement that just won power in the United States election is centered on reversing the gains toward equality and freedom that were beginning to be made in 1964-65.

Part 2, which will follow in a day or so, goes directly into the ideas brought forth from the experiences of women in the Mississippi Summer Project and their import for the gains women made between then and now. That essay will be available only to paid subscribers.

Race & Sex (in both its meanings) in 1964 Mississippi

“After fighting alongside men in a radical movement to correct a grievous wrong, the women then woke up and wondered, ‘What about us?’”

—Susan Brownmiller, In Our Time (1999)

Women who worked in the civil rights movement to assist others in gaining freedom from oppression and injustice were already inclined to shed established gender roles. They came together with men, many of whom were not so predisposed, in one of the more pregnant convergences of the sixties. The offspring issuing from this union would be a feminism considerably more radical than that envisioned by Betty Friedan—born, perhaps a bit prematurely, in Waveland, Mississippi, in the fall of 1964.

Sex and race were intertwined. Each was a very long-standing and powerful hierarchical division. “Right order” as it was defined in American society required that men and white people remain firmly on top and that their position not be challenged. Confronting racial hierarchy was bound to lead to questions about the sexual hierarchy, as had happened more than a century before when the nineteenth-century women’s movement arose out of abolitionism.

The Mississippi Summer Project of 1964 provided an incubator for a radical women’s movement. Forty percent of the project’s volunteers were women. A substantial majority of those women were white. They had been brought up in the age of what Friedan had the year before named “the Feminine Mystique.” While those who sought to join a nonviolent army and go off to a dangerous land were already rejecting traditional gender roles, nonviolence and social reform were traditionally seen as more feminine. In that regard, it was the men in the Summer Project who were going against their expected gender roles, which may have made some of them more intent on maintaining traditional roles for women. When male volunteers sang “black and white together,” they meant on a basis of equality: together horizontally. Many of them were not ready to sing “pink and blue together,” at least not if “together” was taken to imply equality.

“Many people who are very hip to the implications of the racial caste system, even people in the movement,” Hayden and King would write a year after they anonymously broached the subject at Waveland, “don’t seem to see the sexual caste system, and, if it’s raised they respond with: ‘That’s the way it’s supposed to be. There are biological differences.’ Or with other statements that sound like a white segregationist confronted with integration.” For their part, the men against whom the Freedom Movement was struggling were adamant champions of the established roles in both race and sex.

Superiors2 “Screwing” Inferiors2 = Right Order

The issue of interracial sex was the most explosive of all, but it is essential to realize that the taboo was not on intercourse between the races but on a particular version of it. Sexual relations between white men and black women constituted no threat to “right order”; on the contrary, they reinforced it. Putative superiors “screwing” putative inferiors was in keeping with the established system of dominance. A white man having sex with a black woman also served to reinforce the order by reminding black men that they could not protect “their women,” and so were not men at all.

But a black man having sex with a white woman would overturn all order. Worse, from the perspective of insecure white men, it would mean that it was they who could not control “their women” and so were not “real men.” It would constitute nothing less than the end of the world as they knew it and so it must be prevented at all costs.

Mississippi in 1964 has accurately been described as “obsessed” with interracial sex. Fears about the breakdown of segregation were often put in terms of the paramount need to protect white women from black men and prevent the “mongrelization” of the white race. It should not be missed in this context that white men had been “mongrelizing” the black race for centuries by impregnating black women— often forcibly and always through sexual assault in terms of power relationships—during and long after slavery. The lighter complexions of most African Americans in comparison with Africans are the result of this form of interracial sex. As the poet Caroline Randall Williams pointed out in 2020, she and millions of other African Americans today have “rape-colored skin.” Virtually all their white ancestors from the era of enslavement—and most for a long time thereafter—were rapists.

The arrival in Mississippi in the summer of 1964 of a few hundred young white women who would live among the black population was akin to throwing a match into the arid sagebrush that filled the heads of many white males in the state and far beyond. Mississippi segregationists made the prospect of sex between black men and white women a major part of their attack on the Summer Project.

Psychological Emasculation and Views of Women

A man’s most easily accessible symbol of freedom is a woman.

—Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man (1952)

It may be surprising that people who were “hip to” the evils of racism would not also recognize and be against sexism, but many did not. The reasons are complicated, but in one sense also straightforward.

The model for all other dominance/subordination relationships, the oldest, deepest form of asserting supremacy, is the contention that males are superior to females. Across the vast sweep of recorded human history, the primary means to belittle a man has been to declare him to be like a woman and place him in the social position of a woman. That was done through enslavement and continued in the racist hierarchy of Jim Crow after the “peculiar institution” formally ended. African American men were denied all the socially accepted attributes of being a “man.” These include the “three P’s” of being a provider, a protector, and a procreator. Enslaved men could not be providers for their families. They could not protect “their women,” who were subject to the sexual desires of white enslavers, of being sold away, and having their children sold. To be “the Man” was to be in a position of authority. To be a “man” was to be “free.” Being a woman has for a very long time meant not being free.

Enslavement and racism entailed symbolic emasculation. “They [Muslims from elsewhere] had not been aware that [the plight of the black man in America] . . . was a psychological castration,” Malcolm X pointed out after his 1964 pilgrimage. A black man who ignored the rules that prohibited him from acting as a man risked severe punishment, up to and including lynching. All this meant that the desire to be seen as a man, the generally accepted definition of which included being dominant over women, was especially important for many black males. Given the extraordinarily long history of the axiomatic equation of woman with inferior, for a man to accept equality with women seemed to identify himself as an inferior. White men had, purposefully, stripped black men of the socially defined symbols and roles of men, and some black men sought to assert their “manhood” by putting themselves above women.

“A man’s most easily accessible symbol of freedom is a woman,” a black veteran in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man declares. That statement has much wider applicability to men in general, but it was especially the case with black men who had for so long been in what was classified as the female position. The desire—the perceived need—to insist that women are subordinate to men was evident among many of the prominent black men seeking freedom for themselves. “The word man means master,” Cassius Clay (soon to become Muhammad Ali) opined in 1963. “Women don’t take over nothing, unless man lets them. The animals, the trees, the chickens, everything was put here for man. I see women leading men to the dance floor. That’s wrong. The man should lead the woman. The man is the master.”

Becoming Men by Acting like Women?: Sex and Nonviolent Resistance

Nonviolent resistance was and is an extraordinarily nonconformist approach. It was an unconventional way for those on the bottom of the racial hierarchy to challenge those with all the conventional power. It provided a paradoxical way for men to become “men”—free human beings—by acting, to some degree at least, like women.

That the modern civil rights movement in America was generally seen as having started with a woman sitting down and thereby standing up “like a man” is highly symbolic. The movement was based on what would generally be seen as a feminine approach: nonviolent resistance rather than violent confrontation was a means available to those with less raw power than their opponents. Nonviolent resistance was a means of acting by not acting.

The relationship between nonviolent resistance and “being a man” had been a central question for the civil rights movement since its inception in the wake of Rosa Parks’s courageous act of defiance. During his speech to the mass meeting at which the Montgomery Improvement Association was founded and the bus boycott organized, Alabama NAACP leader E. D. Nixon echoed the association of freedom with manhood. “We’ve worn aprons all our lives,” Nixon said. “It’s time to take the aprons off. . . . If we’re gonna be mens, now’s the time to be mens.”

If nonviolent resistance is perceived as unmanly, it is not weak. “This method is nonaggressive physically, but strongly aggressive spiritually,” Martin Luther King Jr. argued.17 Still, Malcolm X was disdainful of the approach. “It’s not so good to refer to what you’re going to do as a sit-in. That right there castrates you,” Malcolm said in Detroit in April 1964. “Think of the image of someone sitting. An old woman can sit . . . a coward can sit, anything can sit. Well, you and I been sitting long enough and it’s time for us today to start doing some standing and some fighting to back that up.” Implying that nonviolent resisters were cowards is absurd, but in a male market that believed violence is “manly,” the case for nonviolence was a difficult item to sell.

The equation man = freedom was enshrined in the nation’s founding Declaration, which proclaimed that all men are equal and free. The tricky part is figuring out what it means to be a man. Crèvecoeur’s 1782 question—“What then is the American, this new man?”—proved to be much more than a rhetorical one. It has been one of the issues around which much of American history has revolved. And it certainly was the issue around which the freedom movements of 1964 and the rest of the sixties revolved: Are males who are not white “men”? Are women “men”? Are those who oppose war “men”? Are males whose sexual preference is other males “men”?

Being a “man” was a constant struggle for middle-class white males emasculated by corporations, for young white males emasculated by a puritanical society, and for black males emasculated by enslavement and racism. But being a man was also a constant struggle for southern white men, who were emasculated by their region’s history: their ancestors had lost a war. And, at least in the American popular mind, no other Americans had ever lost a war. That’s quite a blow to the manhood, even for later generations. Now the damned Yankees were trying to tell them they had to stop emasculating black males and accept them as their equals.

Somewhere in the recesses of the minds of at least some of them, it seems likely a voice was saying, What’s next? Do they want us to say women are equal to us, too? Hell, no!

Some black men emasculated by racism, the society, and economy sought, for a time, to prove their “manhood” through traditionally female means, though many others, especially after 1964, went in the other direction and asserted their “manhood” through traditionally male means.

It is a delicious irony that “unmanly” nonviolence was used to confront and ultimately overthrow a racial/sexual hierarchy that was based in substantial part on the sexual fears of white males. Beyond that irony, the civil rights movement’s emphasis on nonviolent resistance was an important aspect of its relationship with the women’s movement. This philosophy/tactic provided an alternate means of resistance for those for whom violent resistance was not an option. Women are, on average, weaker in the physical areas most useful in engaging in violence and, again on average, they seem to be somewhat less prone to resort to it.

Nonviolence, like the teachings of Jesus out of which it grew either directly or indirectly, through Gandhi, was a particularly feminine philosophy. The civil rights movement showed women that it was possible to succeed in bringing about change through means that were both consistent with women’s traditions and with their lack of the usual instruments of power.

{to be continued}

Fascinating! I've never seen this discussed in this way before, but it makes so much sense. I have been commenting on various Substacks that I subscribe to, that misogyny was a big reason for Harris' loss. Polls don't ask if the respondent is racist or a misogynist because people don't view themselves that way, and they lie. The Washington Post had an essay in the opinion section today by Matt Bai. Basically, Matt was mansplaining why it was wrong to be so upset over Harris not being elected. He stated that woman should be happy that 25% of the Senate is female; this is progress. He also stated that both Hillary and Kamala were not good candidates anyway. I wrote a letter to the Washington Post explaining that Matt was part of the problem. I'm looking forward to reading the next post.